'Hell is Other People'—So, AI to the Rescue?

Alienation, and the pro- and anti-social uses of technology

I once was on a flight from East Asia to New York, sitting in the main cabin. For some reason, there were a large number of babies, perhaps a dozen, accompanied by parents with no other children. The parents were wearing jackets emblazoned with the logo "IOM", a United Nations organization that helps refugees migrate. My initial feelings of warmth towards the humanity on display lasted for about ten hours, which was just a little over halfway through the flight. I couldn't sleep with the near-constant crying of the babies and the frenzied attempts of the parents to calm them. While at that time I was an avid practitioner of Buddhist meditation, and was watching my feelings and wishing others well, I couldn't help thinking whether there was something to the phrase Hell is other people after all.

Is there something inherently yucky about human interaction, that technology can help us avoid? When we, say, order items online rather than go shopping, we benefit from the convenience and efficiency of automation—getting more done in less time, often at less cost. Do we also benefit from shielding our sanity from the vagaries of meet-and-greet with strangers as we head out the door of our home? If so, can AI extend these gains? After all, AI chatbots are getting ever more sophisticated.

Pro- and anti-social uses of technology

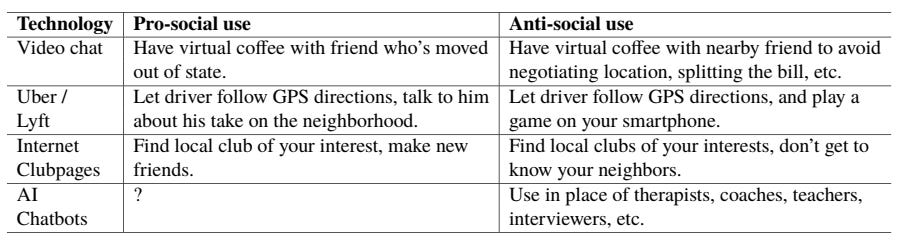

By now, we have a general appreciation of how social media platforms can be a force for anti-social behavior. Jonathan Haidt has argued convincingly on the link between the rise of social media and increasing rates of teen anxiety, depression and self-harm1. But even simpler, and older technologies that mediate human interaction can be used in ways that are inimical to human relations—see above table. For example, one can use 1990s-style online forums to make new friends over a shared niche interest, or as a form of low-input socializing and substitute for offline interactions.

How about AI technology? So far, such technology has been deployed behind the scenes in products of big tech firms like Google and Apple, and have not directly impacted human-to-human interactions. But with the advent of ChatGPT a big change might be in the offing. Sophisticated large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT might enable, for example, an effective customer service chatbot that talks you through a problem with your bill.

It is not clear to me how such AI applications might impact social behavior. They might simply replace rote human interactions that have little to no relational component to them. But if we are given a particular application, how might we go about deciding whether and which use of it is pro- or anti-social? Is ordering items online rather than going shopping, to avoid the minor negotiations inherent in all human interactions, an abuse of technology? More fundamentally, is being stuck in a crowded, noisy airplane cabin hell?

Let's begin with the origins of this essay's titular phrase.

Sartre's HELL IS OTHER PEOPLE!

The line first appears in a play written by the 20th century French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Its meaning there is not quite the same as how we commonly use it these days. Sartre did not mean to simply say that each of us has competing self-interests that inexorably bring us into some level of conflict—for example, we jostle for elbowroom and legroom at our airplane seat. No, Sartre meant something more deeply metaphysical:

All those eyes intent on me. Devouring me. ... So this is hell. I’d never have believed it. You remember all we were told about the torture-chambers, ... There’s no need for red-hot pokers. HELL IS OTHER PEOPLE!2

In the context of the play, and Sartre's other work, the idea here is that we as individuals end up being concerned with others' impressions of us; how we look in their eyes. More so than with our own feelings and emotions. Sartre claims that we lose our free agency in this way, and start acting in "bad faith". We lie to ourselves about what we truly think is the right action in order to get others' approval. In his telling, the mere presence of another person distorts our perception, impinging upon our freedom:

I am in a park, whose objects organize themselves around me, … This bench is to be sat upon; that tree is hidden but demands my gaze. Then suddenly I see another man; and once the park loses its unique distribution according to the principles of my desire, and begins to group itself around his purposes too. The bench becomes a bench that he avoids; the tree a tree that he approaches. ... the other 'has stolen the world from me'.3

Alienation

My longtime readers will notice that Sartre's positions is at odds with this newsletter's. In previous issues I have presented arguments4, citing Hegel, Wittgenstein and others, that our freedom consists in our mutual human relations. Their views, which I find more convincing, indicate that Sartre has it backwards. Our free agency is not opposed by human relations, but stems from it.

If no one talks to us person-to-person, if no one asks us to explain our motivations for our past actions or our future plans, we begin to lose our sense of self and what we are about with our lives. Our horizons and ambitions shrink, and we devolve into living day-by-day on autopilot. In some ways, that feels easier, a surrender. But it is also a little death. Some of us have felt this at times during the 2020 pandemic.

True, we as individuals are affected by what others think. But crucially, these others are others of our kind—a kind that we are part of and get to determine in turn. Stepping back from human relations, either by choice or by eventuality, is an alienation from the sum human body politic that sustains us as individuals. Hell is not other people. Hell is alienation.

Fred Rogers makes this case with more warmth in the latter half of the short video below.

Philosophers have proposed capitalism and science as two forces that push us towards alienation. In a free market, our interactions are through impersonal contracts where we need not have any relations with the counterparty. And in science, the laws of nature favor no one, with no place to call "home" to take ownership of and form a sense of belonging5.

The 21st century has given birth to a third force pushing us towards alienation: internet technology. Even excluding social media, we can note how this technology has severely diminished meeting grounds such as bookstores and movie theaters. Where AI enters this picture remains to be seen.

We are now ready to form an answer to the question posed earlier. How do we judge whether a certain use of technology is pro- or anti-social? We judge by seeing whether it alienates its users, or it does the opposite.

The Opposite of Alienation

And what is the opposite of alienation? Let’s see. I can offer: relating with family, friends, neighbors, community and country; working with colleagues, customers, employers, employees, investors and institutions; learning with teachers and students; competing with athletes and gamers; and exploring art forms with performers and audiences.

Let's use technology and AI in support of these and other kinds of human relations.

I'll end with Tom Cruise's more pithy take here, in the last minute of his recent speech accepting his award at the PGA 2023:

I just got back from filming in South Africa that's a absolutely stunning country and there is a beautiful philosophy.

It's Ubuntu, that originated there and it is the idea that humanity is based on the plural not the singular.

Ubuntu means essentially I am because we are.

And so I thank all of you, and I am, because you are.

Thank you.

PS: While I can write up my thoughts on resolving the question of online ordering (and crowded planes), perhaps I can leave that to readers…

Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid. Jonathan Haidt, The Atlantic. May 2022.

No Exit (French: Huis clos). Jean-Paul Sartre. 1944.

See discussion in Modern Philosophy, p468. Roger Scruton. 1994.

See my earlier post, Even AIs Need Community.

See discussion in Modern Philosophy, p464. Roger Scruton. 1994.