I still remember, from a weekday morning some 20 years ago, a poignant conversation I overheard while on the bus to work. A disheveled man in his mid-30s was on his cellphone. He was speaking into the phone how he was not all that happy those days, and that nights and mornings—especially mornings—were challenging for him. His visage while mostly listless was tinged with despair, and his confession had a pleading tone. Now, getting up that morning to head to work wasn’t all that easy for me either; was I being given a vision of where I might end up myself?

Shooting for the Stars: Elon Musk

“It’s always important to explain the why of things, and the the why of starship is that we want to be a multiplanet species to extend consciousness beyond earth ... [T]here’s also the need to do things that are inspiring and exciting and that give you reason to live. ... reasons to get up in the morning and be excited about the future. And a future where we are a space-faring civilization is infinitely more exciting than one where we are not.”

-Elon Musk1

Musk’s “reasons to get up in the morning” is to “do things that are inspiring and exciting”. I am a start up co-founder, who believes in the meaningfulness of our vision. So I do have a dragon to slay. Even so, I can’t say that that is top of mind for me while getting up in the morning. Upon self-reflection, what I think it typically is, is ... a sense of obligation. Regardless, there’s a much easier critique of Musk’s sentiment: Not everyone at all times has the opportunity to work on something “inspiring and exciting”. How many of us’ calendars this week are filled with civilization moving items? We need a source of purpose that is not so contingent on participating in ground shaking events.

When grappling with a question, it is often edifying two approaches that are diametrically opposed. So I sought to think of a source of purpose that is least dependent on circumstance. And that which came to mind is: faith. Can we take life to be worth waking up for as an article of faith? Meaning, like the three ultimate values of the ancient Greeks—Truth, Goodness, and Beauty—there’s no further reason-giving due:

Why believe X? Because it is True. Why do Y? Because it is Good. Why look at Z? Because it is Beautiful.

The three ultimate values are referred to as such because in their respective modes, once you offer them as explanation, there is a finality to argument. Might *faith* serve a similar function to our question at hand?

Why continue this life? Because I have faith that it is worth it.

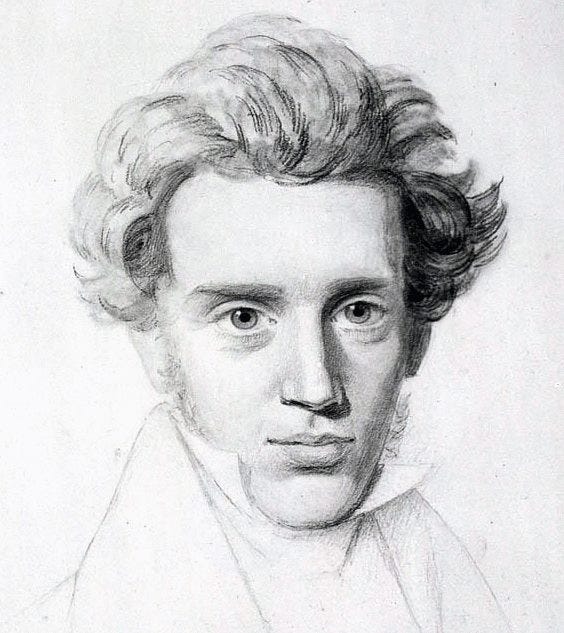

Though practically everyone understands the concept of faith, it is a curious one. While approaches to faith are often incompatible with reason—requiring one to leave their brain at the door—there are philosophical treatments which conceptualize faith as merely independent of reason. Soren Kierkegaard, a 19th century Danish philosopher, called faith incomprehensible. In this take, faith demands a willingness to go beyond reason, but is not unreasonable or irrational.

For example, we can hold the belief “honesty is the best policy”. Such a stance is not amenable to proof; but nor does it infringe upon proof. It can be said to be held on faith. Many life decisions fit this mould. Upon graduating from college in California, I took a job in New York City. Not only was it pretty far from many of my friends who stayed in CA, it was just about as far as possibly can be from my parents and where I grew up. Did I have conclusive evidence that it was going to be the right move for me? No. But nor did I have conclusive evidence that it was not. I had to choose, it was going to be momentous, and I did, and it was.

A book of Kierkegaard’s had a title I found rather suggestive: Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing. So I read it.

Willing the Good: Enter Kierkegaard

The meat of Kierkegaard’s argument begins in chapter 3, where he declaims:

“Purity of heart is to will one thing. ... And he who in truth wills only one thing can will only the Good ...”2

He goes on to note how other things one may will, such as pleasure, fame or even harm, come in many varieties and change with time. What gives pleasure at one time soon ceases to, and we shortly chase after a substitute. Kierkegaard writes that the Good is not like that. And when we will it truly, there is no “double-mindedness”. We do not have a concurrent secret agenda in seeking personal reward or fame, or in avoiding punishment or disrepute. This lack of double-mindedness, the willing of the good for its own sake, ‘purifies the heart’ and brings us peace.

This is strikingly different from Musk’s expression of purpose, his exciting and important venture of space-faring. In comparison, “to will only the good” is so lacking in specificity that it appears reductive. But this same simplicity overcomes the contingency critique of Musk’s expression, for anyone at any time can “will the good”. Kierkegaard offers the case of the sufferer, one who is critically ill and needing others’ help, and says that even she can will the good. Her moral task is no different from a mighty Queen’s. Despite their rather disparate situations, the two find rapport with each other in this common moral endeavor. And the man on his cellphone complaining about his miserable mornings can all the same join them in willing the good, too.

Kierkegaard does eventually write more specifically about how his thesis applies to one’s occupation. But let’s first do a more critical reading and comparative analysis of the thesis itself, which we might summarize as:

Purity of heart is to will only the Good.

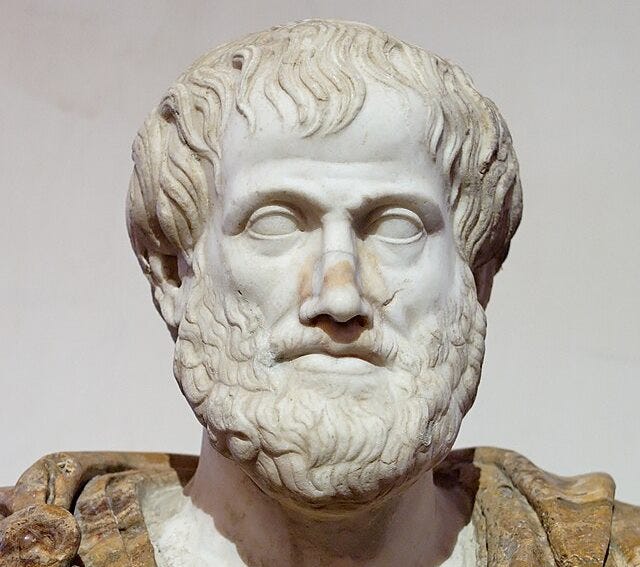

This thesis resembles Aritstotle’s from some 2000 years earlier. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle offered that true happiness is being at work in accordance with virtue3. Virtues are “active conditions of the soul”4 and develop via learning, experience and habit5. They include courage, generosity, temperance, wisdom and prudence. Aristotle does not explicitly discuss purpose or meaningful goals worth striving for. Implicitly, we are encouraged to develop our virtues, for they provide for the highest happiness.

Aristotle does admit that some good fortune is needed for the opportunities to exercise the virtues. If we are in an ordinary life situation that is by and large peaceful and functional, commuting to work on weekdays and running errands on weekends, with paychecks just about covering our expenses and mortgage payments, we may not encounter a situation that calls for courage or allows for generosity. So, Aristotle’s scheme for happiness has drawbacks similar to Musk’s for purpose.

Aristotle’s virtues, however, are better sketched out than Kierkegaard’s ‘Good’. The majority of Nicomachean Ethics is devoted to analyzing the virtues. There are virtues of character, and virtues of thinking. Virtues come with corresponding vices, usually a pair, with one denoting a deficiency and the other an excess. For example, the virtue of courage has the associated vices of cowardice (deficiency) and foolhardiness (excess); the virtue of generosity, stinginess (deficiency) and spendthriftiness (excess). Kierkegaard OTOH actively refuses to develop the concept of the Good.

So, About the Good

“In a certain sense, nothing can be spoken of so briefly as the Good, when it is well described. For the Good without condition and without qualification, without preface and without compromise is, absolutely the only thing that a man may and should will, and is only one thing. ... That which a simple soul, ..., feels no need of understanding in an elaborate way, since he simply seizes the Good immediately, is grasped by the clever one only at the cost of much time and much grief.”

-Kierkegaard, Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing. Chapter 3.

The definition above is, of course, circular with the thesis, and no help to us clever ones. However, we can gather two characteristics of Kierkegaard’s conception of the Good from elsewhere in his book. In chapter 1, he discusses features of “eternal” qualities, and gives the example of immortality. If someone is immortal, he argues, they have to be immortal at all times; not just when they would normally die. Immortality is an eternal quality, not a quality present just at time of death. He concludes that an eternal quality in a person must exist across change, and always has its time. There is a time to work; a time to rest; a time to party. But it is always time for the eternal qualities. By chapter 3, it is clear that he was preparing us to accept that it is always time to will the Good. So Kierkegaard’s conception of the Good is something outside of time, like the number 2.

Secondly, in chapter 3 Kierkegaard insists over and over again that the Good is always one and the same thing. He doesn’t go so far as to say there’s only one right thing to do at any given time, but that there is always only one right thing to will. In this homogeneity, Kierkegaard’s Good is formless.

Timelessness and formlessness. These two characteristics make Kierkegaard’s Good match Buddhism’s concept of emptiness, and also, advaita Hinduism’s non-dual consciousness. Furthermore, Kierkegaard’s disputation style matches those tradition’s anti-intellectual approach. So Kierkegaard isn’t pontificating something entirely idiosyncratic. Nevertheless, this doesn’t help us wrangle a better understanding of what the Good consists in. If Mr. K is too obstinate to oblige, could we consult other philosophers’ work?

A different Mr. K, 18th century Enlightenment-era German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his seminal work on morality, the Critique of Practical Reason, might have something to say here. Hegel and Wittgenstein from the 19th and 20th centuries have made relevant arguments that strongly suggest that the Good has to be socially constructed. We will review these in our next issue, and also get back to the Purity of Heart, for it does have some practical things to say about purpose in one’s occupation.

In Conclusion

Musk’s energizing vision is difficult to fault. For those in a position to participate in that vision, Kierkegaard may very well agree that it is aligned with willing the Good. His philosophy can be seen as generalizing Musk’s vision to everyone at all times, so there is always purpose to be had. While Mr. K’s rhetoric can be somewhat lofty, we shall see what we can make of it from our modern secular point of view, with the aid of other philosophers’ work. Until next time.

At SpaceX Starship flight test, 2025.

Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing. Soren Kierkegaard, 1846. tr. Douglas V. Steere. Chapter 3.

“Happiness is a certain way of being at work in accordance with complete virtue.” Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle. tr. Joe Sachs. Bk 1, Ch 13.

ibid.

Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle. tr. Joe Sachs. Bk 2 Ch 1.